Stop Calling It Tax Reform. It Isn't.

Adjusting rates is a change. We're a long, long way from reform in this bill.

When my boss was first appointed to the Ways & Means Committee, a few things happened immediately. The most notable thing at first was the increase in the ferocity of the lobbying.

On the very same day the announcement was made, literally within a few hours, 3M had emailed to ask for a meeting. She wasn’t even on the committee yet. The next day, two sharply dressed lobbyists sit down across the little table from me in our office. We exchanged pleasantries. “Congratulations!” “Thank you!” “I actually used to work for so-and-so on the committee.” “No kidding! That’s awesome. What a great guy!”

Before long, we were sufficiently chummy and they got down to the reason for their visit. As it turned out, there’s a technical definition for what constitutes an “energy efficient window film” in the tax code. Apparently, twelve of the thirteen window film products that 3M offered back then qualified for a special tax deduction. They were hoping to modify the definition slightly so that it would include their thirteenth window film.

I couldn’t see any obvious reason to object and with a rapidly exploding inbox, certainly wasn’t going to be able to do a whole lot of looking into it. So I thanked them for their time and said I’d pass it along to my boss. That was the last I heard of the window film. It stuck with me though, if you’ll forgive the pun.

Two or three days later, I was asked to come to the Office of the Joint Committee on Taxation. If you’ve never heard of it, that’s ok. I’m not sure they mind. In a nutshell, JCT is the tax policy equivalent of the Congressional Budget Office. CBO provides estimates of the budget impact for any and all legislation coming to the floor that will impact our budget. JCT, by contrast, scores only tax legislation.

Why do we need a whole separate office dedicated full-time just to crunching numbers for tax policy? Why can’t CBO just do it?

Great question. Hold that thought.

After locating JCT’s office, I was ushered into an attractive old conference room along with a handful of other staffers whose bosses were also newly-appointed members of the committee. They sat us down around a long wooden conference table upon which a great many terribly large binders had been placed.

One of the JCT staff members asked how many of us were familiar with “tax expenditures”.

No hands went up. I suspect we were all a little embarrassed not to know. I certainly was.

“It’s ok. Most people have never heard of them.”

Over the next hour or so, they proceeded to explain what a “tax expenditure” is. That is to say, spending through the tax code. We dutifully nodded along at that like we understood what they meant.

We didn’t.

They explained that if the federal government wants to encourage something, there are really two basic ways to achieve that public policy goal. We can spend money through the outlays side of the budget, or we can spend money through revenue side of the budget. That is to say, we can spend money by reducing revenues.

More nodding. Vague understanding coming into view.

And then a simple example finally did the trick: Home ownership. The government really likes home ownership (and home price appreciation) and wants to encourage more of it. So we have a mortgage interest deduction. That’s spending through the tax code - a policy provision specifically and expressly passed for the purpose of subsidizing the purchase of a home. Thus the promotion of home ownership.

To fully grasp the concept, just imagine a scenario for a moment in which instead of getting a tax deduction for the mortgage interest, the government just sent you a check. They’d keep your tax rate unchanged - no deduction - but they’d instead send you a check once a year for whatever the interest deduction would’ve been worth. Would you care? Probably not.

What’s the difference to your bank account? There is none. What’s the difference to the government’s books? Not one red cent. It’s a wash for both parties. The cost of the subsidy is the same and the benefit to you is the same.

But while there is no difference whatsoever for the government’s finances - same deficit and same debt - the political difference is MASSIVE!

Why? Perception.

The public, by and large, hates hearing about massive new spending programs. But a massive new tax cut, on the other hand…. Well… that’s a different story altogether!

So which program do you think a politician would choose to run on if given the choice? Sending millions of lucky homeowners a nice big check every year in perpetuity? Or running on a platform that calls for cutting taxes for millions of hardworking Americans? Same policy. Same cost. Different optics.

See where this is going?

Imagine, if you will, over the course of decades how many times Congress might find itself wanting to spend money on something, but they don’t want to be seen spending money on it.

We can all probably agree that homeownership is a good and wholesome thing, but wouldn’t it seem a little weird to pitch legislation where the government is going to start sending checks out to perfectly affluent and able-bodied people just to help them pay their mortgages? And how do you reckon all those poor bastards who rent are going to feel about it?

Here’s a novel idea. Just pop it in the tax code instead. Boom. Job done.

Or maybe you don’t love the optics of sending taxpayer money to 3M just to make a product they were already going to make and sell to the public anyway. No problem! Just slip it into the tax code.

The concept itself of tax expenditures was pretty eye-opening for me when it was first explained, but it was the scale of all this “spending-but-not-spending” that was absolutely mind boggling. At the time, federal revenues added up to about $2.8 trillion per year and federal outlays totaled about $3.5 trillion. Not bad. Could be better. Except that wasn’t the the real story. The real federal spending on public policy initiatives for that year was actually $5 trillion. But we were spending $1.5 trillion of it through the tax code so nobody really noticed. Myself included.

In short, Congress was actually spending 43% more each year than I had thought they were just an hour earlier when I walked into that room. And mind you I’d been working in Congress for three or four years at that point! I had absolutely no clue. None. If somebody had stopped me on the street and asked me how much the government spends every year, no problem. “$3.5 trillion”. I’d quoted that number dozens of times in dozens of different speeches, letters, etc. In reality, I’d lied through my teeth dozens of time. And the scariest part to me was, I’d had no idea I was lying.

To put the scale of this “spending-but-not-spending” into perspective, last year, tax expenditures were $2 trillion, which works out to about 7% of total GDP. The deficit was *only* 6.4% of GDP. So you could reasonably say that the entirety of the deficit is actually spending through the tax code that nobody notices is actually being “spent”. It doesn’t appear anywhere in writing in the budget. Or more accurately, it’s all right there in the revenue line, you just can’t see it because the spending shows up in the form of missing revenue. Neat trick, huh.

The only way to actually see all this spending - both the scale and what it’s being spent on - is to crack open those binders and start reading. You go right on ahead. We’ll wait.

In every meaningful public policy sense, it is indeed spending. And that’s exactly why the official government documents refer to it as “tax expenditures”. Says so right there in the name. But it’s spending that was never appropriated by Congress and it isn’t renewed annually by Congress meaning that nobody ever really stops to ask if we want to keep “sending out checks” to 3M every year to subsidize their window film business.

These expenditures will never stop unless that specific provision in the tax code has a sunset date and is pre-programmed to expire. And if the provision is structured as a percentage of something as opposed to a set dollar amount, the amount “spent” will grow over time all on its own. And if more people or businesses qualify for the provision (which they have a curious way of doing once they know about it), the spending also grows over time without so much as a single yea or nay.

In short, without anybody needing to do anything at all, in most cases, we will spend more and more and more over time. And the beauty is, nobody even needs to really think about it, let alone fight for it.

In this way, absent a cutoff date, each new provision functions as a new entitlement. If you qualify, we spend the money. Simple as that. So when you hear people talk about the size of “entitlement spending” (usually in the context of us having a big, unsustainable problem), the number they’re quoting for “entitlements” is actually off by a trillion or two per year.

And you wonder how we got into this mess?

Our system wasn’t designed to be on autopilot. Period. Full stop. The Constitution envisioned a system in which Congress has to vote up-or-down on appropriations every year. Increase this, eliminate that. Have a debate. Duke it out.

We hear all the time these days (and rightly so) that discretionary spending as a percent of total spending is 26%. But that’s wrong. That 26% figure is only measuring the discretionary portion of the budget against the mandatory outlays. It doesn’t include the extra 40% odd percent of *actual* entitlement spending we’re doing through the tax code.

How many individual programs and provisions are we talking about? Who knows at this point? Chat GPT would probably have a hard time answering.

As I recall, the entire tax code back then was somewhere on the order of 80,000 pages (and growing very fast). As the American Bar Association pointed out at the time - and this is a direct quote - “the Code has become so long that it has become challenging to even figure out how long it is.” They also observed in the same report that the tax code changes, on average, about 500 times per year - more than once per day.

So unless you’re a lobbyist, tax attorney, accountant, or somebody at the IRS working on a specific provision, all of this is pretty well happening in the background.

Speaking of the IRS, another fascinating meeting I took not too long after my baptism-by-tax code was with the head of the Taxpayer Advocate Service (which is an ironic, but actually wonderful government office within the IRS). The ostensible mission of the Taxpayer Advocate is to be a resource for taxpayers, but I think a more accurate description of their function is to push back as hard as they legally can on the ever-growing madness that policymakers are creating each year. Technically they aren’t allowed to lobby, but this kind of message tends to sell itself once you hear about it. As an aside, I actually take some quiet satisfaction in knowing that some portion of my tax dollars every year go toward paying the salaries of a few good people whose primary job is to tell Congress how insane they are and to gently point out to them that they could stop. There are actually a lot of people in different government agencies with this job. Hopefully DOGE didn’t fire them all.

In any event, by the time I met the Taxpayer Advocate, I was really leaning in hard and listening with both ears. Per the Advocate herself, from her lips to God’s and my ears, individuals and businesses in America spend some 8 billion hours per year complying with the tax code and all its associated regulations (that doesn’t include audits).

It’s such an enormous burden, in fact, that according to statistics compiled by the American Bar Association, if tax compliance were an industry for statistical purposes, it would be one of the largest in the United States, because by their simple math, 8 billion hours works out to about 3.8 million full time jobs.

I honestly don’t know why they brag to Congress about that.

In any case, that was ten or twelve years ago. I have no idea how much worse it is now. And if you’ll forgive me, I really don’t have the inclination to look. What I can tell you is that much like a new, unfamiliar sound emanating from your car’s engine, these things don’t tend to get better with time.

For a recent and high profile example of a tax expenditure, I would direct your attention to the fight over the SALT cap (aka the State and Local Tax deduction), which is all over the news right now because it’s at the very heart of the fight in Congress over the tax bill. SALT is an absolutely massive tax expenditure, even after they capped it in 2017.

It really helps inform the merits of the debate, in my opinion, if every time you hear a politician talk about the virtues of removing the cap on the SALT deduction, just plug in the words “I want to send more of your tax dollars to my wealthiest constituents”. Because a significantly higher cap (and certainly removing it altogether) is really only relevant for their wealthiest constituents. And as we’ve learned, it’s functionally no different than not having any tax deduction at all, but instead choosing to cut those very same recipients a nice big thank-you check - every year, in perpetuity. And in this case, instead of just thanking them for buying a home, we’re also thanking them for opting to make a lot of money whilst living in a high-tax jurisdiction. It’s essentially the taxpayer topping up the bonuses of people work on Wall Street. Why? To pay them to stay in New York instead of moving to Florida.

Everybody cited crime and poor city management for the reasons behind so many people in finance fleeing New York and Chicago for the sunny south. But there’s been crime and lousy management for years. Why move now? Because in 2017, Trump capped SALT and so the federal government stopped “sending checks” to people to pay them to stay in New York.

Do we think the government should send actual checks to these people for this specific purpose? No, we do not. So why send them a check through the tax code?

How, you may ask, did it get to tens of thousands of pages worth of provisions and trillions of dollars in unappropriated mystery spending annually? It’s a very long story and not all of it bad. The simplest answer is the last time the tax code was truly reformed was 1986. Approaching half a century ago. And while I have no idea whatsoever what all is in the tax code at this point, I can assure you we’ve had a lots and lots and lots of new window film added over the years. A billion here. A few hundred million there. Pretty soon it starts to be real money.

I can also tell you that the longer this goes on without real reform to strip all this stuff out, the more inequitable our tax code will continue to get. I don’t think we should underestimate the role this quietly plays over the course of many years in exacerbating wealth inequality in our country. Because aside from the admittedly questionable wisdom of spending trillions of dollars every year without even realizing it, the real true crime from a public policy perspective is that a wildly disproportionate amount of the benefits from tax expenditures - I reiterate, tax code spending - accrue to the top quintile of earners. In fact, spending through the tax code accrues to the top 20% of earners at roughly twice the rate it goes to the bottom 20% (about 14% of all tax expenditures go to the top quintile vs 7% for the bottom quintile).

Again, I think it really helps to visualize it all as a bunch of individual spending programs. Because it is. Imagine if we enacted a new program to send everybody checks each year forever, but we were sending bigger checks to the rich people and smaller checks to poor people. I guess the only reason for the difference is just to thank them for being rich.

Would anybody stand for that? Sending $10,000 checks to the wealthiest one-fifth of Americans every year and only $5,000 checks to poorest fifth? And borrowing the money to do it! No. They would not. There would be riots in the street and I’d probably join them.

While it’s obviously an oversimplification, that is indeed the spirit and and in many respects the basic letter of the law. Just think about the mortgage interest deduction. Young people who can’t afford to buy a home this year are having a portion of their tax dollars sent to the homeowners who could. That’s how tax expenditures work because money is fungible and the debt accrues to all of us.

When we set marginal tax rates for families and businesses, it’s the middle class and small businesses who are by far most likely to pay full freight. The very wealthiest corporations and families are the ones who, by and large, benefit from the bulk of all this complexity in the tax code. They employ armies of tax lawyers and accountants to move money into and out of trusts, move deductions around, “harvest tax losses” as if they’re soybeans and in extreme cases, they’re able to move and/or keep massive sums of money offshore to evade the taxman entirely. And it’s almost always entirely legal. Just google “Panama Papers”. It’s every bit as legal in most cases as it is morally, ethically and fiscally wrong.

Why do multinational corporations have entire office buildings set aside just for their in-house accountants and tax lawyers. It’s not because their books are so complicated. It’s because our books are so complicated.

How many times over the years have we seen examples where a publicly-traded company hops on a Q4 earnings call and brags to analysts about the blockbuster year they just had. With a smile on their face and year-end bonuses in their heart, they’re pleased to announce they’re boosting the dividend and authorizing a new buyback program just to turn right around to the IRS and shrug. “Sorry, pal. No taxable earnings again this year”.

Meanwhile, I can guarantee you that damn near every small business in the country is paying full freight. And probably paying an accountant thousands of additional dollars on top of the taxes just to make sure they’re doing it right! Why? Unnecessary complexity.

Finally, I’d urge you to consider that as a direct consequence of all this hidden spending in the code, marginal rates themselves have to be much higher than they would be without 80,000 pages worth of deductions and loopholes. So, in essence, we have a small business that’s paying 21% instead of 15% and it’s doing so just to make up for the fact that GE is paying 0%. We gotta get the money from somewhere, right?

Here’s a controversial idea: Why don’t we do the spending of tax money in the spending bills and the taxing of people in the tax bills? A system that might end up looking something like this: “You made $100k this year and that puts you in the 26% bracket. That means you owe $26k”. Taxes done. No more figuring out whether the standard deduction is better than itemized. No more subtracting box 6a from box 3b unless box 4 is blank, in which case you should refer to page 12 for instructions. And now we can take our eight billion hours of newly-found spare time every year and go have a good long look at those appropriations bills.

I cannot emphasize strongly enough that the Republican tax bill under consideration right now does nothing to fix any of this basic problem. Not a damn thing. If I had to bet the entirety of my tax refund on it, somewhere in the 1,116 pages of the reconciliation bill being rushed to the floor right now - and probably on more than one page - they’re making the problem worse. Somebody somewhere is getting some window film. Maybe it’s got a sunset provision. Maybe it doesn’t. Either way, I assure you most members of Congress probably won’t ever notice it at all. And if they do, they’ll forget about it soon enough.

The saddest part to me of all this right now is that Republicans had a real chance to simplify things in 2017 (almost a decade ago) and they didn’t do it. Despite the fact they’d been campaigning on simplifying the tax code for at least a decade before that. All of them citing the impact our current code has on small businesses and middle class families. Citing the inherent unfairness and the impact on worsening wealth inequality. Citing the inefficiency and the perverse incentives that cause multinational corporations to keep their capital stuck offshore for years at a time instead of bringing it home to invest in America. I know they campaigned on it because I wrote dozens of speeches and letters for my boss advocating for precisely that. Indeed, part of the reason I didn’t bother looking up more recent statistics is because I relayed this story to her constituents so many times I can still remember all the numbers by heart twelve years later.

But instead of real reform, they’re fumbling around with a three-vote majority trying to shoehorn a TCJA extension into place and every day doing it by throwing around provisions worth hundreds of billions of dollars affecting tens of millions of lives as if all that matters or matters most is getting this bill over the finish line by Memorial Day.

It’s real money, folks. And we don’t have it.

By extending the TCJA and adding to it, they’re also extending the tens of thousands of pages worth of who-knows-what right along with it. My suggestion, as an alternative, is to take your time, sit down with with the Democrats on the tax committees in both the House and in the Senate, pull out a clean sheet of paper, and start from scratch. Make the appropriators justify the spending. That’s their job and frankly, they’re jealous of their jurisdiction and probably salty so much money is being spent through the tax code anyway.

I’m so very proud of this country in so many ways, but frankly we should all be ashamed, in my view, that we’ve let it get this far and go for this long. And really without hardly anyone noticing at all.

While there are certainly plenty provisions in the code that are supportive of growth, I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that the fundamental way we do taxes in this country is not. And at this advanced stage of debt and deficits, I would argue passionately that a tax code that’s enabling trillions of dollars worth of spending on policy initiatives without it ever appearing in the budget where somebody can see it is a tax code badly in need of reform. And this bill ain’t it!

So the next time you hear a politician or a journalist refer to what they’re working on right now as passing “tax reform”, you have my full and complete endorsement to shout whatever expletives you feel are appropriate at the television. Maybe even throw a shoe or a coffee mug as well if it makes you feel better. These people really do deserve it.

Oh, and once you’ve got that out of your system, maybe give your congressman’s office a call and ask the poor staffer who answers how much the federal government spent last year. Then tell ‘em they’re $2 trillion off. It’ll blow their mind too.

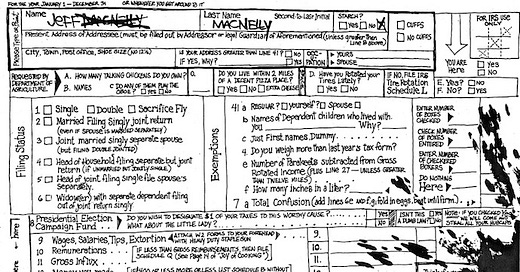

Copyright: Jeff MacNelly (do yourself a favor and view this on a big screen. Then realize this cartoon is 48 years old).

Few topics are more misunderstood in the modern economic discourse than taxes—what they are, who pays them, and what happens when they’re cut. Somewhere between political spin and spreadsheet modeling, we lost the plot.

Let’s get one thing straight: tax cuts don’t reduce federal revenue in absolute terms. What they reduce is projected revenue—a forecast based on current policy, assuming nothing else changes. This is what budget wonks call "scoring," and it’s a game of hypotheticals, not reality.

Here’s where most people get tripped up: our tax system is highly progressive and deeply intertwined with the financialized economy. That means the real driver of tax revenue isn’t the rate—it’s the velocity of money.

When dollars churn rapidly through the economy—moving from consumers to businesses to workers and back again—the tax base expands, and revenues rise. This happens regardless of whether the top marginal tax rate is 37%, 39.6%, or somewhere in between. It’s not just about how much is taxed—it’s about how often money changes hands.

The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) is a perfect case study. Critics predicted fiscal doom. Instead, we’ve seen record-high tax collections—both in total and on a per capita basis. The law didn’t tank revenue; it altered its growth trajectory, temporarily, while the economy recalibrated and capital reallocated.

The hard truth? The federal government is collecting more tax dollars today than at any point in history. Not despite tax cuts—but, in part, because of the economic momentum they helped unleash.

If you're only looking at tax rates and ignoring the velocity of money, you're playing checkers in a chess match.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/200405/receipts-of-the-us-government-since-fiscal-year-2000/

I really enjoyed this Harrison. Lucid and vey well written. My daughter was a staffer for Rodney Frelinghuysen for several years before he packed it in. There are no easy answers, sir. The abyss is too deep now. Imo Trump needs to raise the limit to 40T so he has some running room. The horse is long gone fom the barn. The only reasonable course is to build a bigger barn which means votes that he cannot get without a big beautiful bucket of grease.